Introduction

Faculty members in Indian universities—particularly those mentoring PhD scholars—often find themselves in the position of helping students refine or rewrite technical content for clarity, originality, or compliance with UGC plagiarism thresholds. The challenge is significant: technical content is not as flexible as narrative writing, and altering its language risks introducing subtle errors. For those guiding doctoral candidates in private universities, where research work often blends interdisciplinary fields, rewriting must strike a careful balance between originality and precision.

Technical accuracy is not negotiable. Whether the material involves formulas, statistical interpretations, or discipline-specific terminology, even a small change can affect the reliability of the research. This is why a faculty-led rewrite must go beyond surface-level rewording and focus on preserving the intellectual integrity of the original work.

Why Technical Rewriting Requires a Different Approach

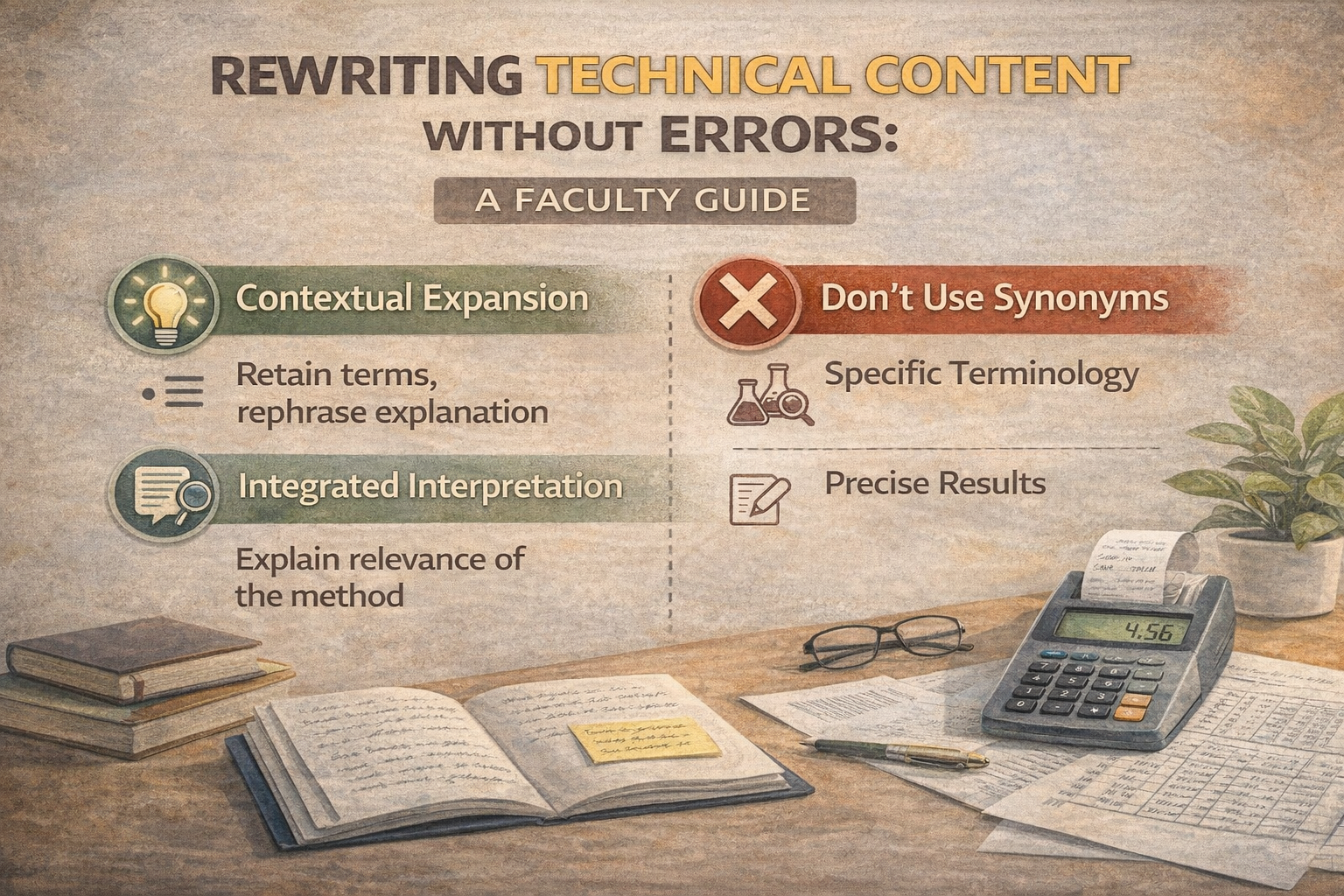

Unlike literature reviews or conceptual discussions, technical sections are tightly bound to established conventions. A physics formula, a statistical model, or a specific methodological term cannot be swapped for an approximate synonym without compromising accuracy. For example, replacing “Fourier Transform” with “wave conversion process” would simplify the term but erase its exact mathematical identity.

In the Indian doctoral context, faculty often guide students who are more comfortable in their discipline than in advanced academic writing. As a result, direct technical accuracy is maintained in their research, but explanatory sentences around it may be repetitive or too closely aligned with reference sources. The goal of rewriting, therefore, is to preserve unchanged the elements that carry exact scientific or mathematical meaning while modifying the surrounding explanations for originality.

Faculty Strategies for Safe Rewriting

One of the most effective methods is contextual expansion—retaining the technical term or equation exactly as it is, but rephrasing the explanation in a way that reflects the student’s own understanding. For example, if the original text states, “The Fourier Transform was applied to convert the signal into its frequency components,” it can be rewritten as, “Using the Fourier Transform, the signal was represented in terms of its individual frequency components for further analysis.” The core concept remains intact, but the structure and flow are different enough to reduce similarity.

Another useful technique is integrated interpretation, where the technical content is paired with a brief statement of relevance. Instead of rewriting only the method, faculty can encourage students to add why that method was chosen. This approach naturally changes the phrasing without altering meaning. For instance: “The chi-square test yielded a value of 4.56” could become, “A chi-square test was conducted, resulting in a value of 4.56, which indicated no significant association between the variables.”

Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Technical Rewriting

The most common risk in plagiarism removal for technical content is unintentional distortion. Even a minor shift in units, numerical rounding, or terminology can lead to a misinterpretation of results. Faculty should caution students against altering reported data for the sake of phrasing variation. For example, changing “p = 0.042” to “p < 0.05” may seem harmless, but it can obscure the exact statistical result.

There is also the temptation to replace technical vocabulary with simpler language to reduce similarity. While this may be acceptable in informal explanations, it is unsuitable for thesis-level academic writing where precision is a measure of credibility. In UGC-approved research formats, repetition of exact technical terms is not penalised, so faculty should reassure students that originality scores are calculated across entire documents, not penalised for repeated key terms.

Cultural and Institutional Context

In Indian private universities, faculty often have to guide a diverse group of PhD candidates—some coming from industry backgrounds, others from purely academic pathways. Those from industry may be strong in technical expertise but unfamiliar with citation practices, while those from academia may write fluently but struggle to express industry-linked applications. Faculty guidance on rewriting must account for these varied backgrounds, ensuring that each scholar retains ownership of the content while aligning with academic expectations.

Furthermore, in many institutions, there is a cultural emphasis on “polishing” the thesis to reflect both originality and scholarly rigor. Faculty members act not only as evaluators but also as co-mentors in shaping how research is presented. Rewriting technical content, therefore, is not just a linguistic exercise but a pedagogical moment that reinforces the student’s conceptual understanding.

Conclusion

For faculty in India guiding PhD candidates, rewriting technical content without errors demands more than language skills—it requires discipline-specific insight, respect for academic precision, and an awareness of plagiarism removal practices that meet UGC standards. By preserving the integrity of technical details while restructuring the surrounding explanation, faculty can help students produce work that is both original and error-free. Done well, this process strengthens the credibility of the research and ensures that technical accuracy remains uncompromised.