Introduction

One of the most confusing aspects of thesis writing — especially for Indian PhD scholars — is understanding what needs to be cited and what doesn’t. With plagiarism software now standard in most Indian universities, students are more cautious than ever. But many still ask a basic question: If I write something that everyone knows, do I still need to cite it?

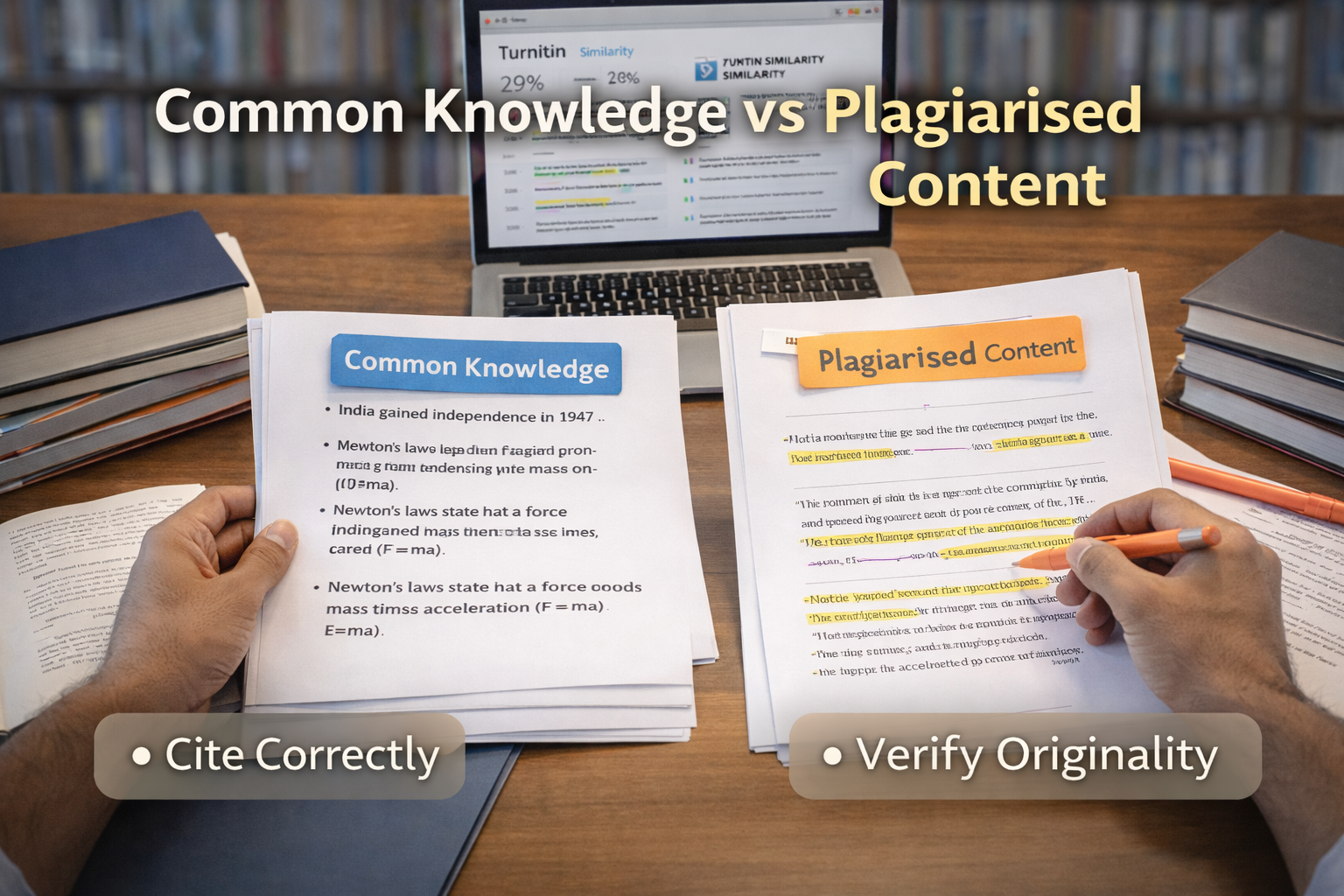

This question opens the door to a deeper discussion about the difference between common knowledge and plagiarised content. It’s a line that many researchers struggle to define. For a first-generation scholar, or someone returning to research after a long academic break, the rules may seem unclear. What is considered common knowledge? What counts as an idea borrowed from someone else? And when does summarising someone’s point without quotation marks become a problem?

This blog offers clarity — in the Indian academic context — on how to confidently write your thesis without crossing ethical lines.

What Is Common Knowledge in a PhD Thesis?

Common knowledge refers to information that is widely known, undisputed, and available in many general sources. You don’t need to cite it, because it’s not tied to a specific person or publication. In an Indian PhD context, this might include:

- Widely accepted facts: “India became independent in 1947” or “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.”

- Well-known theories or models that are decades old: “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has five levels,” or “Mahatma Gandhi led India’s non-violent independence movement.”

- Basic definitions used across textbooks: Terms like “inflation,” “photosynthesis,” or “social mobility” may not need citation if you are using them in a general, introductory sense.

The key test is this: If your average peer in the same field would already know this, and if the idea appears in many general sources without being linked to one author, it is likely common knowledge.

However, when in doubt — cite. Indian universities tend to prefer over-citation to under-citation, especially in early drafts. And if you’re drawing from a specific author’s interpretation of a common concept, it’s no longer common knowledge — it’s their academic contribution.

What Counts as Plagiarised Content

Plagiarism is not just about copying exact sentences. In fact, many Indian scholars are surprised to learn that even paraphrasing without citation can be flagged. Here’s what typically gets counted as plagiarism in a thesis:

- Direct quotes without quotation marks or citations: Copying a line or paragraph from a book, journal, or website without acknowledging it.

- Paraphrased content without citation: Even if you reword someone else’s ideas, if you don’t credit them, it’s considered plagiarism.

- Structure plagiarism: Keeping the same sentence structure or order of points, even if the words are changed.

- Self-plagiarism: Reusing your own published work or previous assignments without mentioning it.

- AI-reworded content that matches sources: Even if you run content through a paraphrasing tool, plagiarism detectors often identify the original structure or close similarity.

In India, where the acceptable similarity index in most universities is between 10–15%, many scholars get flagged for reasons they didn’t expect — especially when they think they’re summarising what “everyone already knows.”

That’s why distinguishing between general knowledge and borrowed interpretation is so important.

A Practical Indian Example: Social Justice in Indian Education

Let’s take an example from the field of education — a common PhD subject in Indian universities.

“The Right to Education Act was passed in India in 2009.”

This is a historical fact, widely known, and available across government websites and school textbooks. No citation needed.

Now consider this:

“The RTE Act reflects Ambedkarite thought by pushing for structural inclusion in school admissions.”

This is someone’s interpretation — possibly from a research article or book. Even if you paraphrase it, you must credit the original source.

Similarly:

“According to Bourdieu, cultural capital influences educational outcomes.”

This line requires a citation because it references a theory introduced by a specific thinker. Even though Bourdieu is well known, his specific theoretical contributions are not “common knowledge.”

In interdisciplinary research — very common in private universities across India — these distinctions become even trickier. What may be common in sociology may not be common in management. That’s why field-specific awareness is necessary.

Why This Confusion Matters in Indian Academia

In India, thesis rejection due to plagiarism is becoming more common — not because students are cheating, but because they don’t understand what to cite and how. Many come from regional-language backgrounds, where referencing culture isn’t strong. Others are working professionals, used to presentations and reports rather than formal academic writing.

Editing and guidance are often limited. Supervisors may not always explain citation norms clearly. As a result, scholars rely on online sources or peer theses — which may themselves be incorrectly written.

This leads to a cycle of fear, over-citation, or accidental overlap. And even good work gets flagged or questioned.

Breaking this cycle requires one thing: confidence in your understanding. Once you know which ideas are common, and which need credit, you can write more freely — without relying on AI tools, random blogs, or risky paraphrasing software.

Conclusion

Knowing the difference between common knowledge and plagiarised content is not about memorising rules — it’s about developing academic maturity. In India’s evolving research ecosystem, especially in private and interdisciplinary universities, scholars must learn to trust their understanding while respecting intellectual ownership.

If a fact is widely known, shared across textbooks, and not tied to a specific author, you can use it freely. But if the phrasing, structure, or insight comes from someone else — whether it’s a journal article or a lecture — it’s only right to give credit.

A good thesis reflects both originality and honesty. And that begins with knowing when your ideas are truly yours — and when they’ve been shaped by others who deserve to be named.