Introduction

For many Indian research scholars, especially first-generation PhD aspirants, the concept of a “similarity score” often enters the academic conversation as an unfamiliar technical requirement. It typically appears during thesis writing or journal submission stages, and more often than not, brings anxiety and confusion. What does this number mean? Who sets the benchmark? Is it a hard rule or a flexible guideline? In a system where academic clarity is not always easily accessible, knowing what is considered an acceptable similarity score in Indian academia becomes essential—not only to meet institutional expectations but also to uphold the spirit of original research.

The phrase “similarity score” refers to the percentage of content in a thesis, article, or dissertation that matches other existing sources. Although this might seem straightforward, Indian higher education institutions interpret and implement these scores differently, depending on the discipline, the nature of the work, and the university’s internal policies. Whether you’re submitting a PhD thesis in a private university or applying for doctoral admission in India, understanding this benchmark helps avoid unintentional academic misconduct and unnecessary delays.

Understanding Acceptable Scores

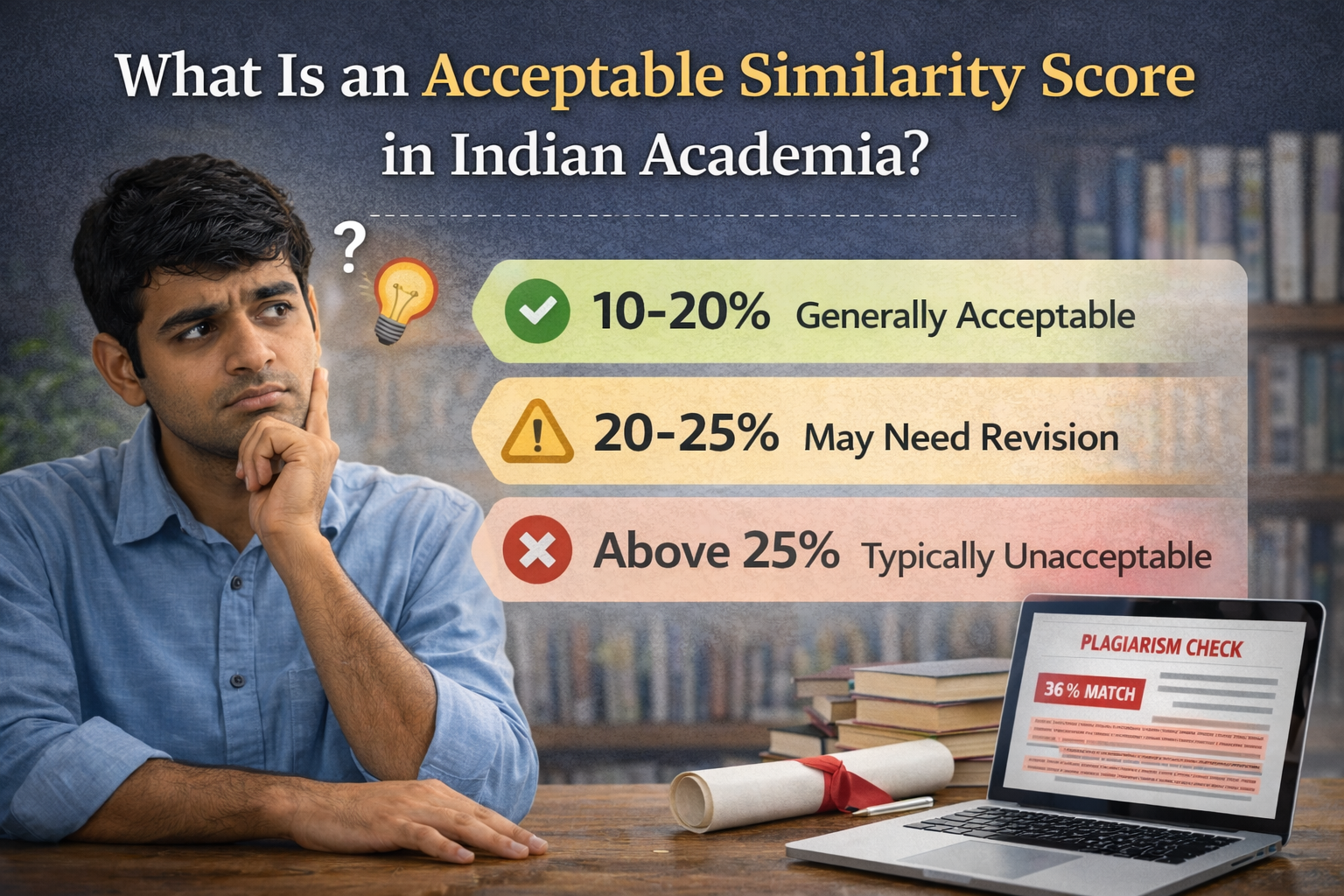

In most Indian universities—public and private alike—the acceptable similarity score generally hovers around 10% to 20%. This range is not uniformly fixed, but it has become a standard reference point for academic departments across disciplines. For instance, a literature review chapter might naturally attract a slightly higher score due to the dense use of terminology and theoretical references. In contrast, methodology or analysis chapters are expected to be more original and thus should show lower similarity. A similarity score above 25% usually prompts revision, and anything above 40% is typically flagged as unacceptable, even in early drafts.

Private universities in India, which are becoming popular choices for working professionals and interdisciplinary researchers, often rely on software tools like Turnitin or Urkund to screen submissions. However, while these tools provide numerical feedback, human interpretation remains essential. Indian evaluators are aware that not all similarity is plagiarism. Matches in references, commonly used phrases, or institutional templates often inflate the percentage. That’s why many universities have internal review mechanisms where supervisors manually verify the nature of similarity before making judgments. It’s also important to note that each institution usually provides access to these tools only a limited number of times, making the first attempt particularly crucial.

Why the Score Isn’t Everything

One of the common myths among Indian scholars is that reducing the similarity score alone is enough to meet academic ethics standards. In reality, the context of similarity matters more than the number itself. A thesis rewritten with synonyms or sentence restructuring—just to reduce the percentage—can still fall short of ethical standards if the underlying work is not genuinely original. Moreover, such rewording often leads to a drop in academic clarity or coherence, especially if done without a deep understanding of the source content.

There is also a cultural dimension to consider. Indian academia places significant emphasis on respect for authorship and intellectual contribution, which means that referencing properly is as important as writing originally. Over-citing without interpretation, or under-citing in the name of originality, are both discouraged. In this context, PhD scholars—particularly those returning to research after a gap or balancing careers and studies—often find themselves walking a fine line between acceptable similarity and academic depth.

In recent years, some Indian universities have begun to include workshops on research ethics, plagiarism removal, and citation practices as part of pre-submission training. These are helpful, but access varies widely. While central universities may offer structured support, many private institutions still expect students to figure it out independently, leading to over-reliance on paid services or unofficial guides. Therefore, understanding the acceptable similarity score is not just about passing a technical check—it’s part of learning how to engage with academic work responsibly.

Conclusion

In Indian academia, an acceptable similarity score is less about a universal number and more about responsible writing. Staying within the common threshold of 10% to 20% is generally advisable, but what truly matters is the authenticity of thought and clarity of expression. Knowing the expectations of your specific institution and discussing them openly with your supervisor is often more effective than focusing on the percentage alone. As academic culture in India evolves, especially with the growth of private universities and interdisciplinary research, the conversation around similarity scores must continue to prioritize ethics over algorithm. That’s where meaningful research truly begins.